Doddington Historic Buildings

Buildings Index | Village Home Page | Pew News

No.3 Doddington Church

Most of the information below is taken from the pamphlet 'A History of The Parish Church of The Beheading of St John the Baptist Doddington, Kent' compiled by Dr Doris W Jones-Baker MA PhD FSA FRSA supplied courtesy of Mary Chastney.

Most of the information below is taken from the pamphlet 'A History of The Parish Church of The Beheading of St John the Baptist Doddington, Kent' compiled by Dr Doris W Jones-Baker MA PhD FSA FRSA supplied courtesy of Mary Chastney.

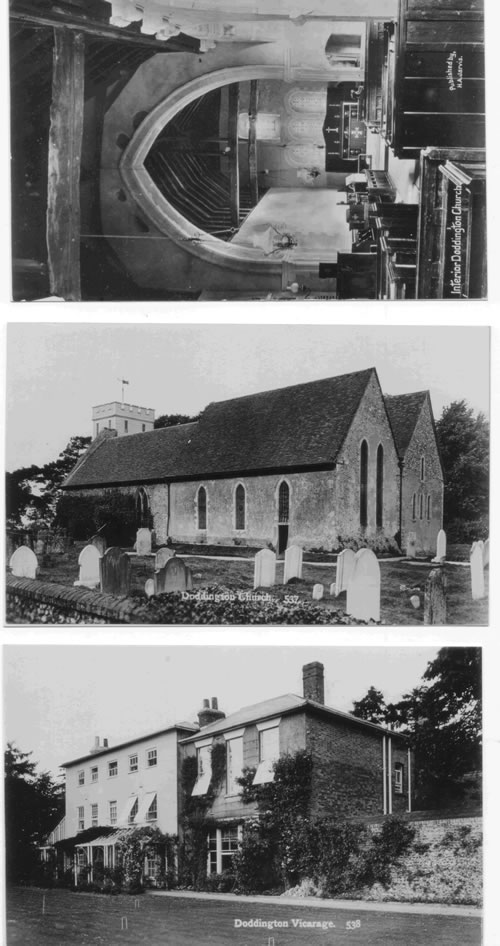

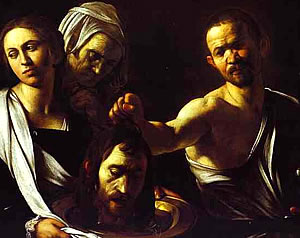

The present church of Doddington is the product of a long history, beginning with it's exterior, of stone dressings and field or chalk flints with their traditional, characteristic Kentish finish of a skim-coat of mortar-dashing that leaves only a quarter of the flints visible, aptly described as a "homely, but highly picturesque and very lasting surface". The principal architectural features of the church today are a chancel, nave, south chapel, south aisle, south porch and weather-boarded west tower.

A medieval church, Doddington is dedicated to the Decollation (beheading) of St John the Baptist. The dedication is one of the rarest in England, shared only with Trimmingham on the East Norfolk coast.

A medieval church, Doddington is dedicated to the Decollation (beheading) of St John the Baptist. The dedication is one of the rarest in England, shared only with Trimmingham on the East Norfolk coast.

A popular saint for medieval church dedications, St John the Baptist was usually commemorated at the Midsummer festival of St John's Eve and St John's Day on 24 June.

However, the Doddington dedication is 29th August, on the feast of his decollation. It may not be the original dedication however it certainly dates from at least 1467 when it is mentioned in the will of James Bourne, of Sharsted Court. "my body to be buried in the churchyard of the church of the decollation of St John the Baptist of Dodyngtone"

Kentish Legend Of St John The Baptist

The obscure choice of dedication suggests a specific reason, perhaps prompted by unusual circumstances. It was not uncommon for medieval churches to have their dedications changed when given a relic associated with a saint (there were numerous 'relics'). Particularly when provided by a benefactor who had been a crusader or pilgrim to the Holy Land. Such relics as objects of veneration in turn drew pilgrims and their gifts to the associated church.

It is recorded by Edward Hasted,( the antiquary of the 1780's) that a stone upon which Christians (possibly St John the Baptist himself) had been put to death, was brought to England during the reign of Richard II (1377-1400). It was kept in the church of St Peter and St Paul at Charing (approx 5 miles south of Doddington). A suggested explanation for the dedication (or re-dedication) of Doddington is that this stone was brought to Doddington and later removed to Charing. The stone disappeared at the Reformation.

History

|

It is likely that a church stood at Doddington in Saxon times. There is a quoin built of tufa in the north wall of the chancel. This calcareous stone cut into blocks was characteristic of kentish building in Saxon and early Norman times.

The church is mentioned in the Doomsday Book of 1086. At the time of the Norman Conquest 1066 Doddington was granted to William the Conqueror's half-brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux but by 1084 it had reverted to the Crown.

Some time after this Doddington Church and living were given to the Archbishop of Canterbury. It may then have become a chapel to the Church of Teynham, (also in the Archbishops patronage.) presumably served by clergy from Teynham.

An instrument of Archbishop Stephen Langdon dated 27th December 1227 recorded in the Black Book of the Archdeacon of Canterbury stated that:

"On account of the slender income of the Archdeaconry of Canterbury, and the affection he bore toward his brother Simon Langdon, then Archdeacon, united to it the churches of Hackington, alias St Stephen's and Tenham (Teynham) with the Chapelries of Doddington, Linsted, Stone, and Iwade, then belonging to it, which churches were then of the Archbishop's patronage...."

Doddington was served by curates most of whose names have been lost. We hear of a Doddington curate in 1229, when Archbishop Richard Wethershed (who had succeeded Archbishop Langdon) confirmed a gift of an endowment, (the first we know of for Doddington church) by one Master Girard. He, while rector of Teynham, had made the gift, and at the instance of Hugh, son of Herevic, had granted to the use of the chapel of "Dudintune" forever, the tythes of the assart (land cleared for cultivation) of Pidinge, that were to be expended by the disposition of the Doddington curate and two or three parishioners of credit, to the repairing of the books, vestments, and ornaments necessary to the said chapel.

Doddington was served by curates most of whose names have been lost. We hear of a Doddington curate in 1229, when Archbishop Richard Wethershed (who had succeeded Archbishop Langdon) confirmed a gift of an endowment, (the first we know of for Doddington church) by one Master Girard. He, while rector of Teynham, had made the gift, and at the instance of Hugh, son of Herevic, had granted to the use of the chapel of "Dudintune" forever, the tythes of the assart (land cleared for cultivation) of Pidinge, that were to be expended by the disposition of the Doddington curate and two or three parishioners of credit, to the repairing of the books, vestments, and ornaments necessary to the said chapel.

In time Doddington became an independent parish with its own vicar. The first vicar listed in Dr Andrew Ducarel's (1713-1785) Index to the Archiepiscopal records of Canterbury Cathedral in the library was one Radhero de Kyngeston, inducted on 16th March 1325. See List of Vicars Upto 2006

The Chancel

The chancel is Norman with early English and later medieval alterations. It may never have had an apse at the east end. By the reign of Elizabeth I the chancel was in disrepair due to the Patron, the Archdeacon of Canterbury, not fulfilling his financial obligations including not supplying an annual donation for parish poor. In 1560 the Doddington churchwardens stated that "The chancel is in decay, Mr Archdeacon is Parson there". In 1562 they complained "The chancel lacketh reparation, the fault thereof is in the Archdeacon of Canterbury" .

The chancel is Norman with early English and later medieval alterations. It may never have had an apse at the east end. By the reign of Elizabeth I the chancel was in disrepair due to the Patron, the Archdeacon of Canterbury, not fulfilling his financial obligations including not supplying an annual donation for parish poor. In 1560 the Doddington churchwardens stated that "The chancel is in decay, Mr Archdeacon is Parson there". In 1562 they complained "The chancel lacketh reparation, the fault thereof is in the Archdeacon of Canterbury" .

In 1563 "The chancel is in great decay for lack of shingling, the fault is in Mar Archdeacon of Canterbury". Some work was finally done on the chancel in 1566 but by 1572 the Doddington churchwardens set out the problem in detail clearly at their wits end: " The chancel is very much in decay. The Archdeacon being the parson there, hath and doth withhold 6s.8d. by year, given out of the parsonage towards  the reparation of the church eleven years. Also half a quarter of wheat by year, given out of the parsonage to the poor of the parish by the space of six years; which money and wheat hath been used to be paid time out of mind, and the same hath been presented very often;' and they can have no remedy therein"(presentments vol.1571-2 Fol.131)

the reparation of the church eleven years. Also half a quarter of wheat by year, given out of the parsonage to the poor of the parish by the space of six years; which money and wheat hath been used to be paid time out of mind, and the same hath been presented very often;' and they can have no remedy therein"(presentments vol.1571-2 Fol.131)

None of the glass in the chancel pre-dates 1572 when the Doddington churchwardens protested again "we present our chancel to be unglazed, so that the minister cannot administer the communion for rain and cold" By 1585 major repairs must have been undertaken for the churchwardens reported only that "Our chancel is faulty, but we will see it amended".

Chancel Windows

Chancel Windows

Of the four windows in the east wall one is above three early English lancets, just pointed, but with round-headed rere-arches.

On the north wall one window of a single light is remarkable for its seven-foiled head. (see image right)

The Low Side Window

The Low Side Window

The most remarkable architectural feature in Doddington church is the so-called 'low side window' at the west end of the north chancel wall. It is a late medieval example of the fifteenth century. Now glazed it was originally fitted with a shutter only. The hooks for hinges and the bolt hole (filled up some time after 1876) remain in the stonework.

To the west of the window, cut in the east face of the recess, is an aumbry, a square cupboard for holding the sacred vessels for the Mass.

To the west of the window, cut in the east face of the recess, is an aumbry, a square cupboard for holding the sacred vessels for the Mass.

Opposite in the east splay, is a small arched image niche above a stone desk with a projection forming a book rest.

No mention has been found for such low windows in English medieval service books, and a variety of explanations have been suggested. Edward Trollope reasoned that a priest within must be ministering to some person, or persons, outside. The window accessories arrangement suggests confession or Holy communion, both under peculiar circumstances. For example if the parishioner was infected with leprosy or the plague. Trollope argued that a practice called 'outer confession' was common, where a person (or persons) could not safely be admitted into the church. The priest could receive confession, pronounce absolution, possibly administered a reserved host via 'the low side window' opening. As an example Trollope referred to the mural painting discovered in Eton College Chapel that represented the converted son of a Jew receiving Holy Communion through such a window.

The Piscina

The Piscina

The piscina (a basin attached to a wall near an altar, where the priest washed his hands and rinsed the chalice) in the eastern wall has only one basin, although there is space for two, while the upper member of its trefoiled head is strangely wide in proportion to its height and to the other members.

Credence

There is also what appears to be a credence (a small shelf, or table near an altar) on the south side of the high altar, instead of on the north as is usual

Bench ends

Of the chancel woodwork, note the four well-carved medieval poppy-head bench-ends.

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

Chancel Arcade

Chancel Arcade

It appears that when the south chapel was built (around 1200) the south wall of the chancel was taken down and rebuilt with a pair of arches a little further south, so that it very nearly aligns with the nave arcade.

The tie-beams of the chancel seem to be original, but lengthened by scarf-joints so as to cover the increased width. Note the coved heading to the eastern portion of the carved oak screen between the chancel and south chapel. Thought probably to have been the canopy of a seat or sedile.

The present sedile is a bench with poppyheads cut vertically to fit against the screen.

Chancel Arch

Chancel Arch

The chancel arch, opening into the nave, has been described as a beautiful example of thirteenth century stonework, lofty, pointed, and just chamfered, on square imposts with moulded abaci and nook shafts east and west. The shafts have rings, and on the capitals, small upright acanthus leaves turning over here and there, to form crockets. Dr Nikolaus Pevsner compared this work at Doddington with that of Master Mason William of Sens at Canterbury between 1175 and 1178, and the beginings of the Gothic style in England.

While none of the medieval architects, masons, or other craftsmen who worked at Doddington church has yet been identified by Dr John Harvey (English Medieval Architects, Rev.Edn.1987) or others, it seems possible that, since Doddington was an appendage of Canterbury, workmen engaged there may have been sent to Doddington among its other parish churches.

The Double Squint

The Double Squint

Pierced through the south pier of the chancel arch is a notable double squint, that gives a view to the altars in both the chancel and south chapel.

Its purpose in medieval times was to enable people in the nave and south aisle to see the Elevation of the Host at Communion, and also to enable a priest standing at an altar between the nave and south aisle to see priests at the two main altars.

The Nave

The Nave

The nave, of three bays, is Norman with Early English additions and later medieval alterations. Surviving features from the Norman period include the north-east tufa quoin, and part of one rere-arch.

South Nave Arcade

The south nave arcade, of three bays and with slightly pointed Early English arches, stands on square piers. (for the fifteenth century alterations to the east pier and arch to accommodate the Rood loft - see below)

The Pulpit

The Pulpit

Historically, the first pulpit of record at Doddington was Elizabethan, and as such older than many in Kent churches. It was already made, and probably fairly new in 1585, when the churchwardens reported of the church that "All is well, except a cloth and cushion to lay on the pulpit".

In the 1960's Pevsner identified the Doddington pulpit as "Jacobean" relying, as he largely did both for church furnishings and fabric, only upon physical evidence for dating. It must be said that there was little stylistic change between late  Elizabethan and early Jacobean woodwork and that most Kent pulpits were indeed Jacobean because of the 1603 directive to churchwardens to provide in every church "a comely and decent pulpit". The present pulpit at Doddington, however, may not be the same one referred to by the Elizabethan churchwardens. It shows no signs of the distressing arising from centuries of wear, and the carving, though fine, is sharp. Possibly it is a good, but modern copy.

Elizabethan and early Jacobean woodwork and that most Kent pulpits were indeed Jacobean because of the 1603 directive to churchwardens to provide in every church "a comely and decent pulpit". The present pulpit at Doddington, however, may not be the same one referred to by the Elizabethan churchwardens. It shows no signs of the distressing arising from centuries of wear, and the carving, though fine, is sharp. Possibly it is a good, but modern copy.

The Reading Desk

The reading desk has notable poppyheads that, however, have lost their finials.

The Font

The Font

The plain hexagonal stone font, unadorned by carving, stands two steps above the nave floor and near the entrance to the present tower. Since medieval fonts were usually near doors (signifying that baptism is the entrance to the Church of Christ) this is probably not its original position.

The sharpness of the stone cutting suggests a modern date (made for the 1855 restoration?) but the wooden font cover, topped by a gilded wooden orb, may well be older.

The South Chapel

The South Chapel

The south chapel at Doddington has been described as a beautiful specimen of later work in the Early English style. It is thought that there was perhaps an interval of half a century between its erection and that of the nave and north and south aisles. the chapel arch is a plainer version of the chancel arch, and contemporary with it, i.e. early thirteenth century, when the south aisle was also widened, and built to span this wider opening.

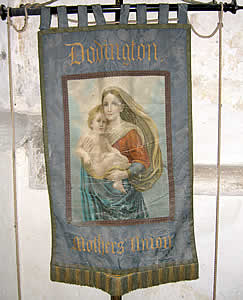

The south chapel was dedicated to St Mary the Virgin, whose Tabernacle (ornamental box for the consecrated elements of the Eucharist that rested in the middle of an altar) was repainted by the will of Isoth, widow of Richard Bourne (of the Bourne's of Sharsted Court) who left the large sum of 6s. 8d. for that purpose in 1515. There were bequests, too, for the light above her altar. Thomas Howchon left it two bushels of barley in 1465, and Richard Fylkes the same in 1473. Note the Early English piscina at the east end in the south wall.

The south chapel was dedicated to St Mary the Virgin, whose Tabernacle (ornamental box for the consecrated elements of the Eucharist that rested in the middle of an altar) was repainted by the will of Isoth, widow of Richard Bourne (of the Bourne's of Sharsted Court) who left the large sum of 6s. 8d. for that purpose in 1515. There were bequests, too, for the light above her altar. Thomas Howchon left it two bushels of barley in 1465, and Richard Fylkes the same in 1473. Note the Early English piscina at the east end in the south wall.

The south chapel belonged to the manor of Sharsted (anciently Sahersted) in Doddington, held of the King in Edward I's time by the service "of the half and one quarter of a knight's fee" and it was, no doubt, built by the ancient family of Sharsted of Sharsted Court, as was customary for such families, as a burial place.

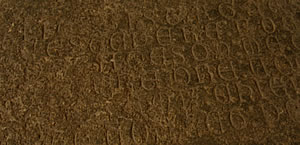

One of their grave stones can still be seen on the chapel floor, the oldest now identifiable in the church, a marble slab with an indent for a floriated cross. This stone had an inscription around the edge in double lines of Lombardic capitals, and by Hasted's time (1782) only the words "..HIC JACET RICARDUS DE SAHERSTADA.." (here lies Richard de Sharsted) could be read.

One of their grave stones can still be seen on the chapel floor, the oldest now identifiable in the church, a marble slab with an indent for a floriated cross. This stone had an inscription around the edge in double lines of Lombardic capitals, and by Hasted's time (1782) only the words "..HIC JACET RICARDUS DE SAHERSTADA.." (here lies Richard de Sharsted) could be read.

One or more of the old grave slabs in the chapel pavement, however may have been inverted, and others, now plain, might have belonged to the Sharsteds, who were lords of Sharsted manor until the death of Robert in 1333. He left a daughter as heir, who married John de Bourne of Downe Court in Doddington (of the ancient Kent family of Bourne of Bishops' Bourne) and son of John de Bourne, Sheriff of Kent in the reign of Edward I

A second ancient stone, but of Kentish rag, and also with an inscription in Lombardic characters across its head, now in the chapel floor, was originally in the demolished north aisle of Doddington church, now part of the churchyard, where it was dug up in 1855. The six-line inscription in Norman-French forms a rhyming quatrain commemorating the maiden Agnes, who probably belonged to Sharsted Court or one of the other Doddington manors.

A second ancient stone, but of Kentish rag, and also with an inscription in Lombardic characters across its head, now in the chapel floor, was originally in the demolished north aisle of Doddington church, now part of the churchyard, where it was dug up in 1855. The six-line inscription in Norman-French forms a rhyming quatrain commemorating the maiden Agnes, who probably belonged to Sharsted Court or one of the other Doddington manors.

It reads :

ICI : GIST : AGNES : DE : SUTH

CESTE PERE : UOUS : IRREZ : T

OUZ A MESON : ME : COUENT : DE

MORER E : ORE : UOUS : PRIE : ZY

ATER : AMY : CHIER : LE : MAIE : MO

RTE : UOILLET : PENSER :

Translated by Archdeacon E. Trollope and read by him in reporting the discovery of this stone to the Archaeological Institute at London in 1855 :

Translated by Archdeacon E. Trollope and read by him in reporting the discovery of this stone to the Archaeological Institute at London in 1855 :

" Here lies Agnes, under this stone,

All go to the house where I am gone,

Hither hasten, friend most dear;

Think of the poor dead maiden here"

A Mystery

One of the gravestones in the chapel floor has been deliberately defaced to remove the inscription (see above right pic.). Why, when & by whom is unknown

South Chapel Brasses

South Chapel Brasses

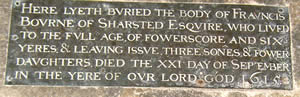

Apart from the indent for the now lost brass of a foliate cross on the slab of Richard de Sharsted, only one brass remains in the south chapel. This is the inscription in English on the stone of Francis Bourneof Sharsted, Esq. who died in 1615 aged 85, and left issue three sons and four daughters.

Medieval Paving

Some medieval paving remains in Doddington church, notably a number of floor tiles in the south chapel.

South Chapel Windows

South Chapel Windows

The most notable architectural feature in the chapel is its fine Early English windows. In the east window, of two lancet lights, some of the glass is original. The thirteenth century circular medallion shows the departure of the Holy Family for their flight into Egypt.

This was used in the 1855 restoration as the starting point for glazing the lancets. Above the east window there is an exquisitely moulded label that is terminated by little corbel heads. They are not placed at the spring of the label arch, but the label there takes a horizontal course for about three inches, before it ends in these pretty corbels.

The South Aisle

The South Aisle

the south aisle, contemporary with the demolished north aisle, is Early English. Originally much narrower that it is today, it was widened on the south side to the same width as the south chapel in the early thirteenth century.

the south aisle, contemporary with the demolished north aisle, is Early English. Originally much narrower that it is today, it was widened on the south side to the same width as the south chapel in the early thirteenth century.

South Aisle Windows

Of the two south aisle windows, the older, of two lights, in the south wall is late Early English, contemporary with the widening of the south aisle.

The larger west window, of three lights, is later, belonging to the decorated style (roughly corresponding to the reigns of Edward I through Edward III) divided by mullions, and the head ornamented with bar tracery making geometrical, flowing shapes.

The South Door

The South Door

The stonework of the south door is contemporary with the widening of the south aisle at the beginning of the thirteenth century.

The south door wood-work, and its lock, as noted by Arthur Hussey in 1852, were medieval, but the present door is modern.

The South Porch

The low buttressed south porch, but with later alterations, may have been built when the south aisle was widened at  the beginning of the thirteenth century.

the beginning of the thirteenth century.

The Tower

the earliest medieval tower at Doddington for which we now have architectural evidence stood to the north of the present tower. It opened into the middle of the nave by a wide, pointed gothic archway that all but spanned the width of the nave, the remains of which are still to be seen in the west nave wall.

Standing on a hillside above the village, Doddington church, and especially the tower, has had little protection from storms through the centuries. Nor is it surprising that the medieval tower was in need of repair as early as 1507, when Andrew Dungate of Downe Court left 3s.4d. "to the raparation (sic) of the Bell Tower" .

Standing on a hillside above the village, Doddington church, and especially the tower, has had little protection from storms through the centuries. Nor is it surprising that the medieval tower was in need of repair as early as 1507, when Andrew Dungate of Downe Court left 3s.4d. "to the raparation (sic) of the Bell Tower" .

Toward the beginning of the Civil War, in the autumn of 1643, occurred probably one of the greatest calamities to befall Doddington church. The steeple on the tower was struck by a "tempest of lightning" and "burnt down", the bells had fallen and lay on the floor "all broken and cracked". The wonder is that the entire church was not destroyed by fire.

The difficulties of rural parishes in raising large sums for repairs are perennial, and the Doddington churchwardens' presentments for the rest of the seventeenth century and beyond tell of the hard struggle to make good the damage. There are no records of anything being done until after the restoration of Charles II in 1660. At the Archdeacon's court in 1664 Doddington churchwardens Edward Gurney and Robert Peckenham stated that it was "true" that the steeple was "ruined" and explained that "the parishioners are not of ability to repair the same, it being almost twenty two years since it happened, whereby the work will be very chargeable, insomuch that half the rent of the land in the parish will not be sufficient to do it".

In the first part of the eighteenth century the medieval tower was at last repaired, and a steeple erected, for Edward Hasted wrote in his 'History of Kent' 1782 that at Doddington church "At the west end is a low, pointed steeple in which hang six bells".

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, however, the tower, no doubt having been found to be unsafe, was taken down. It was replaced cheaply by a smaller, lower, and wooden weather boarded structure with wooden battlements on top and standing on a stone base somewhat to the southward of the medieval tower. The expense was met by selling four of the six bells mentioned by Hasted.

The Lecturn

The Lecturn

With brass inscription at base :

"To the Glory of God,

and in affectionate remembrance

of the men in our village who gave their lives for their country

1914 - 1918

Presented by the

Members of the

Doddington Mothers Union

1918

Names of the Fallen

Wilfred Carryer James Davis Percy Sorscer Leonard Jarvis Harry Philpot |

Sidney Kite Frank Mills Sydney Pullen William Seager Richard Smith Frederick Mungeam " |

The Bells

Dungate's will of 1507 is the first we hear of the medieval bells in Doddington's tower. Later accounts of them in churchwarden's presentments show that there were four and that their combined weight was estimated at about "forty hundredweight" (Presentments of 1560, vol.1560-84 Fol.38)

Although in 1664 the judge advised the churchwardens to send out a "brief" to other parishes asking for contributions for repair of the Doddington steeple and bells " ...and for a flagon for the communion which they say is yet wanting...." again in 1678 Doddington protested that "the parish is not able to repair the steeple and mend the bells and hang them as required..." The parish was finally driven to selling the ruined medieval bells for bell-metal, for which the Vicar himself, Daniel Somerscales, petitioned the court in person on May 24th 1695, which was granted. In May 1698 churchwarden William Skeene reported that the bells had been sold for £77 17s.6d. but still the matter dragged on. On October 9th 1701 the parishioners agreed that "£3 be yearly made up and placed for the increase of a sum for new bells"

When J.C.L. Stahlschmidt wrote his 'Church Bells of Kent' in 1887, there were still only two bells at Doddington church, both of the eighteenth century, and but one of them, according to the Vicar, Ref. W.J. Monk, "in ringing order". Stahlschmidt listed them as :

"I.,31-in ROBERT CATLIN FECIT 1751

II.,33-IN. RICHARD PHELPS MADE ME 1712"

The second bell now bears the following additional inscription:

"RE CAST 1962

CHRISTOPHER VEAZEY VICAR

CHARLES LEESE CMG

CHURCHWARDEN CYRIL SMITH"

The Medieval Church

The Medieval Church

The Medieval High Altar

The medieval chancel, or high altar would have been dedicated, as was customary, to the patronal saint: John the Baptist and his Decollation. We hear of this altar, and its light, in the wills of Doddington's benefactors. In 1465 Thomas Holmeston left a bushel of corn for the benefit of St John's light, that is, toward the cost of tapers or candles. In the same year Thomas Howchon left it two bushels of barley. In 1507 Andrew Dungate (the Dungates of Dungate Street in Kingsdown had succeeded the Bourne's at Downe Court "about the latter end of King Henry VI's reign" - he died in 1471) left the substantial sum of 4d to St John the Baptist's light.

The Lost North Aisle

The nave once had two medieval aisles. traces of three pointed arches of a demolished Early English north arcade have been found on the exterior of the north wall. We do not know when or why this north aisle was taken down.

Lost Medieval Shrines

In the medieval Doddington church there were at least three lights for altars and images whose dedications are now known, but whose locations have been lost. These, identified from fifteenth and sixteenth century bequests, were probably situated in the nave or the south aisle. Most unusual was the Alms Light, of which, in Kent, only one other is known - in the large church of St Clement, Sandwich. In 1478 William Mayhew left 4d "To an Almes Light in the church" at Doddington. In the fifteenth century the Doddington Herse Light received at least two bequests. In 1465 Thomas Howchon left two bushels of barley "To the lights about the Herse" and in 1473 Richard Rylkes one bushel of barley "To the Herse Light" . At the beginning of the sixteenth century, and probably earlier for this "popular" saint, there was also a light to St Katherine, to which Andrew Dungate of Downe Court left 4d in 1507.

The Rood

The Rood

before the Reformation, set high above the east end of the nave, was the Great Rood (crucifix) that would have been accompanied, on either side, by large painted or gilded images of the Virgin Mary and St John the Evangelist, and possibly other saints as well. In some medieval churches the Rood and saints figures were suspended from the roof, but from archaeological evidence it appears that at Doddington they probably stood on the carved oak Rood beam that spanned the chancel.

The Rood Beam

From fragments of the medieval Doddington Rood Beam (the largest 5'4"long) discovered among the timbers in the nave roof in 1902 and 1907 - a most rare discovery in England - it is now possible to reconstruct its appearance with detailed information about dating, size, position, design and decoration. The Rood Beam was found to have been thus 12.5" in height from edge to edge, and 3" in width.

It was indeed fortunate that these fragments of the doddington Rood beam were examined by the antiquary and the twentieth century authority on Rood beams, lofts , and screens, Aymer Vallance FSA (of Aymers, Sittingbourne, whose family had for centuries been associated with Kent) since the fragments themselves were "lost' during the change of vicars at Doddington in 1920. Vallance published a photograph of the fragments in his monumental book 'English Church Screens Being Great Roods Screenwork & Rood-Lofts of Parish Churches in England & Wales (1936) plate 12. It is from Vallance's discussion there, and his lecture to the Society of Antiquaries in London where he exhibited two of the fragments, that our information now comes.

According to Vallance, a complete pattern of the carving could be made out, a purely architectural design that "appeared to have been executed shortly before the middle of the thirteenth century" He explained that :

"The design.. consists of an arcade of trefoil-cusped arches, wide in proportion to their height, with an average centering of 10.5 inches. From the crown of the arch to the level of the springing measures 5.5 inches While the columns are short and sturdy, not exceeding 4.5 inches in height, capital included, down to the bottom. The capitals and bases are of plain moulding. The carving exhibits little attempt at modeling, but is in simple, low relief throughout, except where a good effect of depth and shadow is obtained by the workmanlike device of a bold, angular hollow, sunk from the extremity of each cusp to the opposite point in the arc."

The arcade design on the Rood beam showed no sign of a stop at either end, nor were there any mortise holes on the under surface, that suggested support only at the ends, probably, as was usual, sunk in the walls, and not attached to any substructure of Rood loft or screen. The upper face of the beam, however, had two mortise holes in the fragments alone, centering three feet apart and 4.25 " and 4.75" long, probably to help support figures of saints standing above. Since the beam was carved, if with a somewhat variant design, with equal finish back and front, it must have been fixed to be seen from two sides, east and west.

The Rood Lights

At Doddington, as in other parish churches, it was customary to burn lights such as lamps, branches and candelabra before the Great Rood. These were usually suspended from the roof by cords or chains, and were maintained by regular parish funds, if not, provided for by individual benefactions. We hear of four such bequests at Doddington at the end of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth centuries. Two bushels of barley were left to the "Light of the holy Cross" by Thomas Howchon (1465) and Richard Rylkes (1473) while in 1499 Joan, Widow of Robert Okynfold, left it "a taper of wax," and in 1507 Andrew Dungate of Downe court left "To the High Cross one ewe".

The Rood Screen

Below the Rood beam, but as we have seen not attached to it, was a wooden Rood Screen, whose design has been lost. The base of the Rood screen, however remains, worked up into the box pew on the south side of the entrance.

The Rood Loft

Above the Rood screen stood the Rood loft, at Doddington a gallery made of wood erected in the fifteenth century that extended across the nave and the south aisle. Rood lofts were usually constructed in the later medieval period when the introduction of "priksong" (part-singing) into the services required a larger number of singers, and also a place for an organ or other instrumental accompaniment.

While nothing now remains at Doddington of the Rood loft itself, the fifteenth century alterations made to the stonework, especially the easternmost nave arcade, to accommodate it are still to be seen. The object was to provide headroom in the loft so that people might walk from the "gangway" above the east end of the south aisle across to the Rood loft in the nave unobstructed by the intervening arcade without the difficulty of cutting a passage through the stone arcade spandrel. The method used at Doddington was to take down the east side of the east arcade, and rebuild it so that the arch would spring from a higher level. Thus, the impost on the east side was made 3'10" higher than that on the west side and the imposts on the other two arches to the west. The resultant "rampant arch" and other distortions to the stonework, now all too visible, were masked by the Rood loft's parapet. However disfiguring today, these medieval alterations for the Roof loft at Doddington are of notable architectural interest as illustrating the peculiar arrangement to circumvent low arcades that was largely confined to Kent parish churches. Other examples are at Lynsted, Sittingbourne, Tenterden, Biddenden, Cranbrook, and Aylesford.

The Rood Loft Stairs

At Doddington access tot he Rood loft was by a (probably narrow) stairway, traces of which have been found toward the east end of the south wall in the south aisle.

The Sanctus Bell

Before the Reformation Doddington, like most churches, had a Sanctus, or as it was popularly called "Saunce" bell which would have been sounded at the Office of the Mass, as the priest said the opening words of the Sanctus ("Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord god of Sabbath...") so that all might make adoration. The Sanctus bell was generally hung so that its sound might be heard both inside and outside the church. Often the Sanctus bell was in a cote on the gable of the chancel roof, or in a window, and its rope led down into the chancel for convenience of the server at the altar. In some churches, more awkwardly, one of the bells in the tower was used.

How the Doddington Sanctus bell was hung is unknown. These bells were usually small and it is recorded that the Doddington bell was larger than usual from its description. In 1560 the doddington churchwardens presented on Arnold Whitlock, then of Lynsted, but formerly a Doddington churchwarden, who, as they stated "hath a great saunce bell from our church"

Erasmus's Paraphrases

Whitlock, like many another at the chaotic time of the Reformation, had an easy way with church property, but however regrettable his thieving, the contemporary descriptions of such takings are often the only historical records we now have of them. A grasping man, and quite unrepentant, Whitlock was again presented by the doddington churchwardens for theft twelve years later:

"1572 That Arnold Whitlock now dwelling in Lynstead, did take away a Paraphrase in Queen Mary's reign, and hat not restored the same again"

In the reign of the Protestant Edward VI, an English translation made in 1548 of the great reformer Erasmus 'Paraphrases of the New Testament' (written between 1517 and 1524)was ordered to be placed in all parish churches beside the Bible.

Doddington Churchyard

The only feature of Doddington churchyard to have attracted the interest of historians was a remarkable ancient yew tree that was still growing there at the beginning of the eighteenth century. another of the parson-scholars who visited Doddington in times past, the Rev. John Harris, D.D. and F.R.S, described it in his 'History of Kent' (Vol I p.100) in 1719, as follows :

The only feature of Doddington churchyard to have attracted the interest of historians was a remarkable ancient yew tree that was still growing there at the beginning of the eighteenth century. another of the parson-scholars who visited Doddington in times past, the Rev. John Harris, D.D. and F.R.S, described it in his 'History of Kent' (Vol I p.100) in 1719, as follows :

"In the Church-yard are three Yew Trees; out of the body of which grow a dozen, or more, of the large arms of a poplar tree; whose spreading branches compose almost all the lower part of this oddly double tree; the yew appearing above in the upper part of it; so that it hath a body and top of yew; but most of the lower and middle branches are of the white poplar; it seems to have come into this state from some accidental conveyance of the poplar seeds into its hollow body (perhaps by the means of the birds dropping them there) where meeting with some old rotten sullage or earth they took root and grew"

The churchyard also contains the fine eighteenth-century tomb of Edward Bentham of the Navy Office, London. His connection with the parish was not known until information contributed by Jeremy Greenwood October 2007 as follows:

" Will of Edward Bentham, of the Navy Office London 20 May 1774 PROB 11/997

He was Chief Clerk in the Ticket Office (Pay Office) and was the son (born 1714) of Brian Bentham, Clerk of the Cheque at Sheerness.

the connection is;

Nicholas Adye, esq. the third son, succeeded to Downe-court, and married Jane, daughter of Edward Desbouverie, esq. Their eldest son, John Adye, succeeded to this manor, at which he resided till he removed to Beakesborne, at the latter end of Charles II.'s reign, about which time he seems to have alienated it to Creed, of Charing, in which name it continued till it was sold to Bryan Bentham, esq. of Sheerness, who devised it to his eldest son Edward Bentham, esq. of the Navy-office, Since his death this estate has by his will become vested in trustees, to fulfil the purposes of it.

From: 'Parishes: Doddington', The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 6 (1798), pp. 307-16. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=62972&strquery=Bentham"

Tomb of Edward Bentham  |

Info Held by English Heritage (contributed by Peter Stuart)

DODDINGTON Church Lane (east side)

Church of the Beheading of St John the Baptist

Grade I listed Parish church.

12th Century, extended south c.1200 and 15th Century, restored 1873 and in 1907.

Flint with timber framed and weatherboarded tower and plain tiled roofs. Nave and south aisle, chancel and south chapel, west tower and south porch. West tower on flint base, with 2 early 20th Century weatherboarded upper stages, battlemented, with gothick traceried lights. Buttressed south porch with plain chamfered doorway. 15th Century Perpendicular and 14th Century 'Y' tracery windows in nave and aisle, with 3 lancets in south chapel south wall and 2 large eastern lancets.

Chancel east wall with 3 small lancets with one over. Nave North wall with blocked north door repaired brick buttressing. Exposed tufa quoins and blocked arches in chancel north wall possibly to a lost chapel and tower.

Interior: at the west end of the nave, blocked chamfered west doorway, west window and part blocked re-arch of 12th Century window. Three bay arcade on chamfered arches on square piers. Crown post roofs in nave and aisle. Chancel arch with drip mould arch over on moulded square imposts with attached clustered shafts, with rings and acanthus crockets, the right hand pier with squints to chancel and south chapel. Arch from south aisle to south chapel simple chamfered arch on square imposts. Chancel with 2 bay arcade to chapel, slightly chamfered on round piers with square, moulded abaci. Round headed re-arches to chancel east windows. 15th Century re-arch to north-west window of chancel taken to floor level, blocking earlier lancet, to enclose stone reading desk and aumbry, perhaps a confessional. South chapel, the lancet reveals with drips and double moulded surrounds with attached shafts, carried on string course. South east respond brought to floor level to enclose doorway. Fittings: Chancel with round headed pisina, cusped aumbry 15th Century bench with half-poppy heads used as sedilia, with 15th Century screen to chapel or 22 lights, the end coved to form a canopy over the sedilia; 15th Century wooden reading desk with poppy heads. Octagonal jacobean pulpit, 15th Century octagonal font with 17th Century wood cone cover. Boxpews survive in nave and south chapel, with raised and fielded panelling.

Wall paintings, in chancel on lancet responds large 13th Century figures. Some fragmentary 13th Century glass.

Monuments: South chapel with medieval slabs on floor incised with Latin crosses, 1 with brass inscription to Francis Bourne, d.1615. Wall monument to George Swift, d.1732, of white marble, with grooved Doric pilasters, cornice, with enriched frieze and broken pediment clasping vase. Small black plaque on wall behind pulpit to John Adye, d.1612, with scrolled base and cornice with achievement over. chest tomb . Dated 1756. Stone with marble top, the chest with raised rectangular panels with chamfered corners, and rectangular vases at corners, on double plinth. Inscribed to Edward Bentham, d 16th May 1774 also his wife Margaret died 3rd Sept 1756.

Info from the late Mrs Mary Chastney (resident of Doddington) courtesy of Les Roberts:

Letter to Mrs Chastney from Ken & Jean Davis re pictures below